“Time is just memory mixed with desire…”

~ Tom Waits, “The Part You Throw Away”

Languorous and fluid, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood floats along currents of longing that seem to come to us straight from deep in Tarantino’s psyche, a place where the Los Angeles of 1969 is real and alive and appealing and sad. Broadly, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is about Hollywood the Dreamland and Hollywood the Reality and the impossibility of reconciling the two. Or, to take a different perspective, it’s about the impossibility of Tarantino reconciling himself to himself.

Much has been made of the film’s rewriting of history, but I think to receive the climax of this film in the way that you might receive the ending of Inglourious Basterds or Django Unchained completely misses the way this film, unlike those, goes to great pains to set-up its resolution differently; in Basterds and Django, their resolutions were the natural outgrowth of a clear build towards a narrative goal, an expression of catharsis that the entire film had been building toward. This film has no such clarity in trajectory; it ambles about from scene to scene, sequence to sequence, before the finale arrives. When it does arrive, it does so with a sharp tonal shift, and, unlike the prior films, goes out of its way to underline just where this film is breaking away from history. In case you missed his maneuvers before, Tarantino concludes his motion picture with the plaintive, ghostly strains of Maurice Jarre’s cue, “Miss Lily Langtry” (lifted from The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean), before “Once Upon a Time…” appears on the screen.

Some commentators have lamented that Tarantino isn’t interested in Sharon Tate as a person, but Sharon Tate the Human Being could never be reanimated by a filmmaker, and Tarantino himself is assuredly aware of that fact. One of the film’s most memorable scenes presents us with Margot Robbie-as-Sharon Tate watching the real Sharon Tate on-screen in a film, celebrating the real Sharon Tate while clarifying that whoever Margot Robbie is playing is very much not the real deal. He applies similar exaggeration to every other “real life” figure that appears in this movie (among them, Steve McQueen and Bruce Lee): these figures are the screen icons that live in Tarantino’s mind, not the persons who lived and breathed and died.

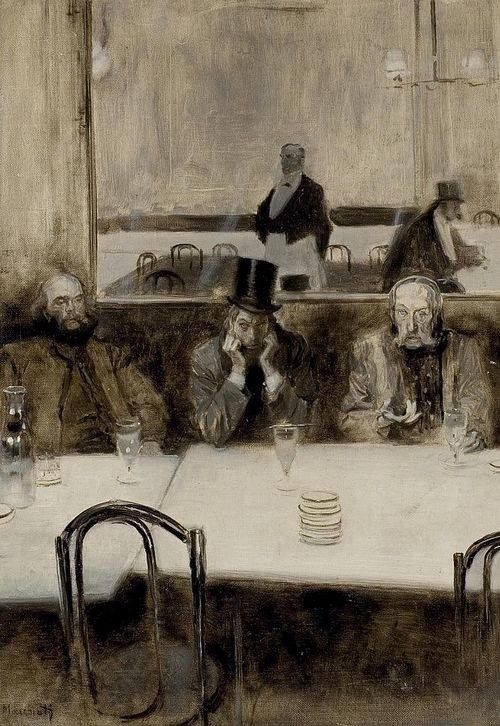

Protagonist Rick Dalton, a second-rate actor in the midst of a breakdown, is directly fictionalized, but he, too, is a creation drawn from the biographical details of real-world also-rans that filled Hollywood, as is his stuntman and best-friend, Cliff Booth. Theirs is a dysfunctional, broken bromance, a struggle to navigate a dysfunctional, evolving Hollywood by clinging on to each other. The Hollywood they navigate is Tarantino’s Hollywood: a place alive with the pop culture miscellany that Tarantino adores. Real life intrudes on the nostalgia: this is the home of alcoholics and maybe-murderers, haunted by the dark menace that lives in the abandoned film sets on the fringes of Los Angeles, but it’s also the place where people could drive in cars with the radio blaring and might end up at a theater or drive-in with a luminous marquee that happened to be showing a beat-up film print of a Spaghetti Western. The latter mightn’t balance out the former, but that doesn’t change the depth of love Tarantino has for it.

The fantasy of Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is a fantasy that the also-rans of culture that Tarantino cares about–not just the actors that nobody talks about anymore, but the shows and old theaters and even the radio commercials–actually matter. But in the end, it’s just a daydream, as flimsy as daydreams are. Reality is what it is, and no level of imagination can change it. That won’t stop Tarantino from trying.